We occasionally veer away from chronicling our winery visits to discuss some of the more interesting (confusing, odd?) aspects of wine and wine tasting. We’ve covered wine aromas, fun wine tasting stereotypes, barrel tasting, tasting room etiquette, bottle-your-own activities, even creative ways to get to wineries. We’ve even dipped our literary toe into confusing grape varietals. Now we take on a phrase that gets thrown around a lot in tasting rooms that can cause confusion: malolactic fermentation. Strap in, here we go!

Tasting wine is easy, but understanding everything that a wine guide says can be challenging. Some terms are obvious, like French oak versus American oak when barreling. But there is a lot of science behind the art of wine making, and high school chemistry class was a long time ago in a far distant galaxy. Just relax, we can learn a bit about this malolactic fermentation thing without any Bunsen burners or lab coats.

Malolactic fermentation is usually mentioned while tasting wines with “soft” and “buttery” feelings on the tongue. Nearly all red wine undergoes malolactic fermentation, but it is rarely mentioned. Most sparkling and nearly a quarter of white wines get malolactic fermentation, so it is something of a discriminator among these varietals. The first time I heard about malolactic fermentation, my overactive imagination brought up images of Mallo Cups and cold glasses of milk. Turns out that I was a bit off on that imagery.

So the whole ‘malolactic fermentation’ thing is about reducing unpleasant flavors in wine. All wine naturally contains some amount of malic acid, which can imbue a harsh flavor. Longer, hotter growing seasons lead to wine with less malic acid, while cooler climates produce wine with more malic acid. The malic acid makes the wine taste sour or tart, with a “puckery” or over-dry tongue feel. This creates something of a marketing challenge if not corrected.

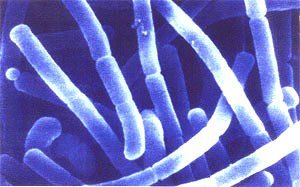

|

| Lactic acid bacteria |

Malolactic fermentation converts malic acid to lactic acid. Molecule for molecule, lactic acid is less acidic (it’s a chemistry thing) and a smoother, most say buttery, mouth feel. This transformation from one acid to another is accomplished by a micro-organism called lactic acid bacteria (not a very creative name, yes). This tiny beast eats malic acid and, um, excretes lactic acid.

Lactic acid bacteria (let’s call it LAB from now on, OK?) exists naturally in the vineyard. That said, most wine makers choose to eliminate the natural LAB with a dose of sulfur dioxide during the crush phase and “inoculate” their wine with a specific strain of LAB, called Oenococcus oeni, at a specific time of their choosing.

|

| Inoculation begins! |

Some wine makers add LAB early in the process, when they add the yeast. Others wait to add their LAB until the yeast fermentation is over. In either case, the malic acid levels go down and the lactic acid levels go up. That means more butter and lest tartness. Mission accomplished!

The only side effect of this procedure is the cloudiness that all this eating and excreting leaves behind. No worries, though, a bit of bentonite or other fining agent will drop the cloudiness to the bottom of the barrel and allow crystal clear wine to be racked (a fancy word for pumped) over to a fresh barrel.

So there you have it, the secret story of malolactic fermentation. The next time you’re in a winery and encounter a buttery Chardonnay you can casually say, “Nice butter notes, malolactic fermentation, right?”

Cheers!

About the Author: John grills a mean steak and is always in the market for another wine fridge. Believes that if a winery has more than 10 employees, it's probably too big. Buys wine faster than he drinks it, but who cares?