By the time wine makes it to our table, it is safely ensconced in a bottle or (gasp) a box. In many cases, though, the road to the table goes through an oak barrel. Oak barreling is by far the most popular way to age wine, but did you ever wonder why, or how? Here is what you should know!

The journey from grapes on the vine to wine in the bottle is a long one. After harvest, crush and primary fermentation, the wine needs to age to remove the rough edges and develop its more attractive characteristics. This aging can happen in a wide variety of vessels, including stainless steel tanks, concrete eggs, and quite commonly, oak barrels.

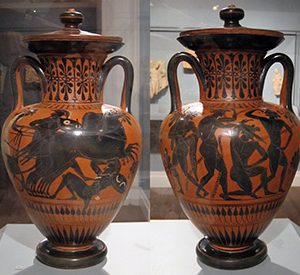

Thousands of years ago, wine was a very popular alternative to unsanitary water. It was typically aged and stored in clay vessels. The clay kept the wine from leaking or evaporating away, but did nothing to improve the flavor. Additionally, the heavy clay jugs were fragile and difficult to seal. The ancient Gauls discovered that oak was an ideal material from which to build barrels to store their beer. What worked for the Gauls storing beer worked for the conquering Romans storing wine. An industry was born!

Oak is an ideal wood for wine barrels. The wood is soft and pliable enough to easily form into the curved staves that form the familiar bulging barrel sides. Further, the fine grain of oak makes it less porous than other soft woods, meaning that less of the precious wine evaporates during aging.

Oak is an ideal wood for wine barrels. The wood is soft and pliable enough to easily form into the curved staves that form the familiar bulging barrel sides. Further, the fine grain of oak makes it less porous than other soft woods, meaning that less of the precious wine evaporates during aging.

There are three primary “nationalities” of oak used for wine barrels: French, American and Hungarian. Each has unique characteristics that winemakers can use to craft specific flavors in their wine. French oak (Quercus robur if you took A.P. Biology) is widely used, imparting very subtle flavors.

American oak (Quercus alba) isn’t as fine grained as French oak, and adds more assertive flavor elements. Due to the perversity of marketing, American oak is quite popular in France while French oak is all the rage in America. Picture enormous ocean-going freighters full of new, empty barrels passing each other in the Pacific.

Rounding out the barrel triumvirate is Hungarian oak (Quercus robur). Yes, that’s right. Hungarian oak is actually the same species as French oak. There are some differences because of climate, but it is fundamentally the same wood. Hungarian oak is appreciated because of the spicy notes it imparts, along with its substantially lower purchase price.

Making barrels is quite an involved process. Raw staves are cut to approximate size and air dried for up to two years. Once cured, the rough staves are cut to precise shapes, with the ends narrower than the middle, and exactly the same length. Each barrel is made from 24-36 staves, depending on size. The staves are attached to one circular barrel end and fastened with a metal band. The barrel is formed into its rough shape by hammering a metal band down the body of the barrel.

The curvature of the barrel staves is achieved by spraying the inside of the barrel-to-be with water and then setting a small fire inside. The heat and moisture makes the staves flexible. Using a series of screw clamps, the barrel is slowly formed into its final shape. An hour or so of careful work and a barrel is made!

The final step in barrel making is the toasting. That is the process where the inside of the barrel is burned slightly to improve its interaction with the wine. Depending on the winemaker’s preference, the toasting can be done to various degrees (cleverly named light, medium or heavy toast). Light toasting presents more of the natural wood surface to the wine, giving it a stronger oak and butter flavor. Heavier toast gives the wine a smoky or spicy flavor.

New barrels have a pronounced impact on the wine. The influence of the oak drops by about half every year it is used. That means that after about three years, the barrel has a negligible effect on the wine, earning it the label “neutral oak.”

Imparting that lovely oak influence doesn’t necessarily require using an oak barrel. Oak barrels cost from $600 to $4,000 each. Although they can be used for 100 years, they still represent a major expense to a winemaker. That has created quite a market in alternative approaches.

Oak can impart character to wine in nearly any form. Many times large stainless steel tanks get long planks of oak, mesh bags of oak shavings, or even powdered oak essence suspended in the wine. This gives the winemaker very complete control over the oak’s impact on the resulting wine, without the expense of barrels.

So there you have it; the inside story on the wine barrel. The next time a wine guide talks about a “lightly toasted French oak” barreling for a wine, you can nod sagely and ask if there has been any experimentation with Hungarian oak. You will sound SO wise!

You’re welcome!

About the Author: John grills a mean steak and is always in the market for another wine fridge. Believes that if a winery has more than 10 employees, it's probably too big. Buys wine faster than he drinks it, but who cares?